Squats: Benefits, Muscles Worked, Types of Squats & More!

Squats have played a pivotal role in helping me become a professional athlete and maintain a high level of performance for over a decade.

From air squats to heavy back and front squats, jump squats, Bulgarian split squats, and even full pistol squats at 6’10”, I’ve used nearly every variation to build strength, stay healthy, and develop the athleticism needed to compete year after year.

Learning how to squat properly is one of the most important things anyone can do for their body.

Whether your goal is to move better, reduce knee pain, improve athletic performance, or build an aesthetic physique, mastering the squat will get you closer.

I’ve performed thousands of squats throughout my career—not just to get stronger, but to keep my knees pain-free, improve my posture, and increase my mobility.

In fact, I consider squats one of the best long-term tools for preventing injury and boosting total-body strength and resilience.

For most people, goblet squats are the ideal starting point—they teach proper form, improve biomechanics, and offer just the right amount of loading for mobility and strength development.

But for athletes and performance-driven individuals, front squats and back squats are two of the best exercises for building raw power and lower-body size.

Bulgarian split squats are one of my personal favorites for building single-leg strength, and pistol squats are a true test of single-leg strength, mobility, balance, and athletic control that, yes, even at 6’10”, I used to do regularly.

Squats are more than just a leg exercise—they are one of the most effective compound movements for naturally increasing testosterone and human growth hormone, building total-body muscle, improving cardiovascular conditioning, and speeding up your metabolism.

They are essential for athletes, but the truth is, anyone who improves their squat mechanics and uses different squat variations will experience dramatic benefits in their health, strength, and body composition.

What Are Squats?

Squats are a fundamental compound exercise that mimic one of the most natural human movement patterns: sitting down and standing up.

At their core, squats involve bending the hips, knees, and ankles simultaneously to lower the body, and then extending those same joints to rise back up.

They are one of the most effective full-body exercises because they engage multiple major muscle groups—including the quads, glutes, hamstrings, calves, and core—while also developing coordination, balance, and mobility.

Squats can be performed with just your bodyweight or with external resistance like dumbbells, barbells, or machines.

In both athletic and clinical settings, squats are used to build strength, improve function, increase power, and prevent injuries.

They’re also a primary exercise for developing muscular hypertrophy, enhancing athletic performance, and supporting long-term joint health.

Whether performed as part of a beginner’s fitness routine or in a high-level training program, squats are one of the most valuable tools for improving overall physical health and performance (Stone et al., 2024).

How to Do Squats Properly

Although there are many different types of squats—each with their own specific setup, posture, and purpose—they all share fundamental principles that form the base of good squat mechanics.

Whether you’re doing a bodyweight air squat, loading a heavy front squat, or elevating your heels for better mobility, proper squat form is essential for safety, performance, and long-term joint health.

Each squat variation changes how your body loads and moves—shifting the emphasis to different muscles, joints, or motor patterns.

I’ll break down the form cues and benefits of each variation below, but before that, let’s start with the most foundational squat of all: the air squat (or bodyweight squat).

This is the perfect place to start for beginners and a useful movement for athletes during warm-ups or conditioning circuits.

It builds mobility, reinforces ideal biomechanics, and teaches your body how to move efficiently under tension without load.

How to Do a Squat

- Start in an athletic stance:

Stand tall with your feet roughly shoulder-width apart. Point your toes slightly outward (around 5–15 degrees) depending on your hip structure and comfort. - Engage your core and set your posture:

Brace your core as if preparing to take a punch. Maintain a neutral spine, keeping your chest proud and shoulders relaxed. - Initiate the movement from the hips:

Push your hips back slightly like you’re sitting into a chair. Then allow your knees to bend and track outward, staying aligned with your toes. - Lower under control:

Descend until your thighs are at least parallel to the floor—or deeper if your mobility allows. Aim to keep your heels grounded and your weight evenly distributed across your feet. - Maintain knee and torso alignment:

Your knees should never cave inward (valgus). Keep your torso upright, but naturally inclined forward—don’t try to stay completely vertical. - Drive up through the heels:

Press firmly through your heels to return to standing, squeezing your glutes at the top without overextending your lower back.

A properly executed squat recruits nearly every major muscle group in the lower body, along with your core and spinal stabilizers.

More importantly, it trains the neuromuscular coordination needed to move safely and efficiently in both athletic and everyday life (Straub & Powers, 2024).

This foundational technique forms the basis for more advanced squat variations, and mastering it is the first step toward building a stronger, more resilient body.

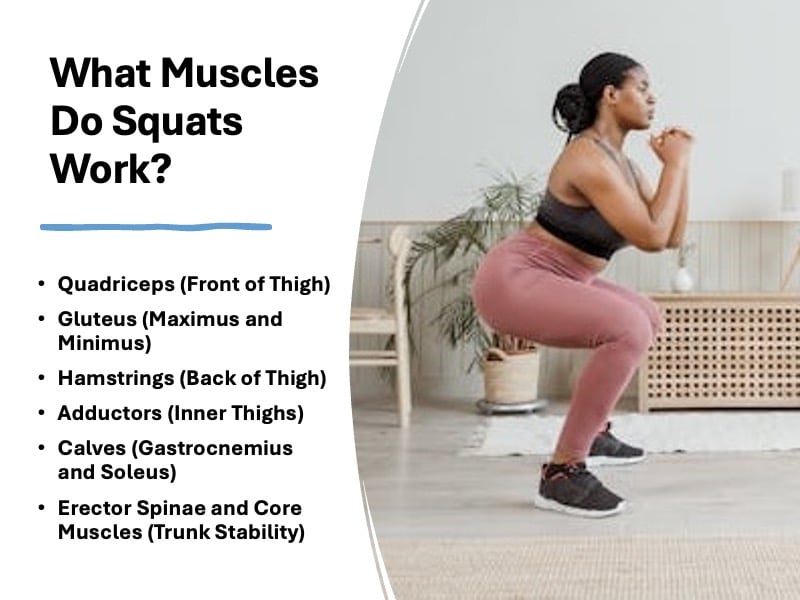

What Muscles Do Squats Work?

Squats are a full-body movement that emphasize the lower body but also challenge the core and spinal stabilizers.

They activate multiple muscle groups simultaneously, making them one of the most efficient exercises for building strength, power, and coordination.

Here’s a breakdown of the primary muscles worked during squats:

Quadriceps (Front of Thigh)

The quadriceps are heavily involved in the extension of the knee joint as you rise from the bottom of the squat.

Deeper squats increase quad recruitment due to the greater range of motion.

Variations like front squats, goblet squats, and heels-elevated squats place even more demand on the quads.

Gluteus Maximus (Buttocks)

The glutes are the powerhouse of the squat, driving hip extension and contributing significantly to upward propulsion.

The deeper the squat, the more glute activation you get.

Back squats, Bulgarian split squats, and box squats are excellent for glute development.

Hamstrings (Back of Thigh)

While not the primary movers, the hamstrings stabilize the hips and knees during the descent and help with hip extension on the way up.

Squat variations that involve a forward torso lean, like low-bar back squats or Zercher squats, can increase hamstring engagement.

Adductors (Inner Thighs)

These muscles help stabilize the hips and assist in controlling movement during the descent and ascent.

In deeper squats, especially sumo or wide-stance squats, the adductors play a larger role.

Calves (Gastrocnemius and Soleus)

The calves provide ankle stability, particularly at the bottom of the squat, and help maintain balance throughout the movement.

Although not a primary driver, they’re crucial for controlling descent and supporting joint alignment.

Erector Spinae and Core Muscles (Trunk Stability)

The spinal erectors and core (including the obliques and transverse abdominis) work isometrically to stabilize the spine and prevent excessive forward lean.

Loaded squats—especially front squats, Zercher squats, and overhead squats—significantly challenge your core and postural strength.

Benefits of Squats – What Are Squats Good For?

Squats are one of the most effective exercises for developing total-body strength, athleticism, and long-term physical resilience.

Whether you’re training for peak performance, rehabbing from an injury, or just looking to move and feel better in daily life, squats deliver measurable benefits that extend far beyond building leg muscle.

Loaded and full-depth squats are especially powerful in creating long-term physiological adaptations.

As noted by Stone et al. (2024), these adaptations include increased tissue stiffness, cross-sectional area (CSA), and improved force transmission across joints—making squats a cornerstone for both performance enhancement and injury reduction.

Here’s a detailed breakdown of what squats are good for:

Building Lower-Body and Core Strength

Squats are one of the most effective exercises for developing foundational lower-body strength, especially in the quadriceps, glutes, hamstrings, and adductors.

These large muscle groups are responsible for nearly every athletic and functional lower-body movement—from jumping and sprinting to walking up stairs and picking something off the ground.

As you lower into a squat and return to standing, your glutes and hamstrings work to extend the hips, while the quads extend the knees and stabilize the joints.

The adductors support pelvic stability, especially during deeper or wider-stance squats.

In addition to your lower body, squats require strong core engagement to maintain an upright torso and protect the spine.

Deep core muscles like the transverse abdominis, obliques, and erector spinae work isometrically throughout the movement to resist spinal flexion and stabilize the trunk under load.

Because squats are a compound movement, they recruit more muscle fibers and require more systemic coordination than isolation exercises like leg extensions or leg curls.

This results in superior strength development, improved joint control, and increased athletic efficiency.

Improving Athletic Performance

For athletes, squats are an indispensable tool for developing explosiveness, stability, and raw power.

A well-structured squat program improves:

- Acceleration off the line

- Sprint speed and stride length

- Vertical jump height

- Agility and lateral quickness

- Force absorption and redirection

Loaded squat variations—especially front squats and back squats—build rate of force development (RFD), which is critical for sprinting, jumping, and cutting.

Deep squats, in particular, improve muscle-tendon unit stiffness and stretch-shortening cycle efficiency, both of which translate directly to better athletic performance (Stone et al., 2024).

Squats also improve neuromuscular coordination, teaching your body to generate maximal force in minimal time.

This means that not only do you get stronger, but you get better at expressing that strength explosively and efficiently in sport-specific movements.

Additionally, unilateral squat variations like Bulgarian split squats and split squats develop balance, core stability, and single-leg strength—critical traits for basketball players, soccer athletes, sprinters, and just about any sport where power transfer happens one leg at a time.

Whether you’re trying to dunk a basketball, cut faster on the court, or just stay bulletproof through a long season, squats should be at the center of your strength and performance training.

Supporting Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation

When performed correctly, squats increase the mechanical strength of muscles, tendons, and bones.

This boosts joint stability and enhances your body’s ability to absorb force.

Deep squats, in particular, have been shown to improve tissue resilience and reduce the risk of lower-body injuries.

Squats are commonly used in rehab protocols because they promote joint integrity and restore functional movement patterns (Straub & Powers, 2024).

Improving Functional Movement and Daily Life

The squat mimics natural, everyday motions like sitting, lifting, and standing.

Squat training improves coordination, balance, and mobility, making everyday tasks easier and safer—especially as we age.

Regular squat practice enhances independence and physical confidence in both athletic and non-athletic populations.

Promoting Hormonal and Metabolic Health

Squats stimulate the release of key anabolic hormones like testosterone and human growth hormone due to their high neuromuscular demand and recruitment of large muscle groups.

This hormonal response supports muscle growth, fat loss, and metabolic health.

Additionally, high-rep squat training can significantly elevate heart rate and oxygen consumption, improving cardiovascular fitness and metabolic rate (Hong et al., 2024).

Building Muscle and Improving Body Composition

Squats are one of the most effective exercises for stimulating muscle growth and transforming body composition.

Because they engage multiple large muscle groups at once, they create a strong anabolic stimulus—promoting muscle protein synthesis and increasing lean mass over time.

Squatting under load (especially with progressive overload and full range of motion) activates fast-twitch muscle fibers that have the greatest potential for hypertrophy.

Variations like back squats, front squats, and Bulgarian split squats are particularly effective at building dense, functional lower-body muscle.

Additionally, squats cause a significant hormonal response, increasing levels of testosterone and human growth hormone, which are key regulators of muscle growth and fat metabolism.

This makes them an essential tool for building muscle, reducing body fat, and improving overall body composition.

Because of their full-body demand, squats also burn a high number of calories during and after your workout.

This post-exercise metabolic boost (known as EPOC or excess post-exercise oxygen consumption) increases fat oxidation and helps support long-term fat loss goals without sacrificing strength or lean tissue.

When programmed intelligently—combining heavy sets, moderate volumes, and high-rep conditioning work—squats offer one of the best returns on investment for anyone trying to build a strong, athletic, and aesthetic physique.

Increasing Bone Density

One of the most underrated benefits of squatting is its powerful role in improving bone mineral density, which is essential for long-term skeletal health, injury prevention, and overall vitality—especially as we age.

Squats place mechanical stress on the bones of the hips, spine, and legs, which stimulates osteogenesis, or new bone formation.

This is especially true for loaded squats, where the spine and lower limbs must bear and stabilize significant weight.

According to Stone et al. (2024), high-intensity resistance training like squats contributes to structural adaptations in bones and tendons, increasing their stiffness, cross-sectional area (CSA), and resistance to mechanical strain.

Over time, this kind of axial loading not only strengthens muscles and connective tissue, but also enhances bone strength and density, helping to reduce the risk of fractures and osteoporosis.

This makes squats particularly beneficial for:

- Older adults looking to maintain mobility and avoid frailty

- Women, who are at higher risk for age-related bone loss

- Athletes recovering from immobilization or bone-related injuries

- Anyone interested in preserving long-term joint integrity and structural health

Squatting with proper form, progressive resistance, and a full range of motion is one of the most accessible and effective ways to stimulate skeletal adaptation and support lifelong musculoskeletal health.

Reduced Joint Pain and Stiffness

Despite common misconceptions, squats—when performed correctly—can actually reduce joint pain and stiffness, especially in the knees, hips, and lower back.

Instead of causing wear and tear, squats help restore natural joint mechanics, improve mobility, and enhance tissue resilience.

The key lies in proper form, full range of motion, and smart progression.

Deep squats, in particular, have been shown to improve neuromuscular function, reduce stiffness, and minimize discomfort over time when compared to partial or half squats.

A 2020 randomized controlled trial found that full-depth squats produced significantly lower pain and stiffness and greater improvements in strength and functional performance than partial-range variations (Pallarés et al., 2020).

Squats also strengthen the muscles that support and stabilize joints, such as the glutes, hamstrings, and quadriceps.

This balanced muscular development reduces uneven forces on the knees and hips—often a root cause of chronic pain and joint degeneration.

As someone who’s dealt with the physical toll of professional basketball, I can confidently say that squats have been a cornerstone in my own joint health routine.

Many of the squat variations I regularly use—such as goblet squats, Bulgarian split squats, and box squats—are also on my list of the best exercises for knee pain and knee injury prevention.

When taught and progressed properly, squats aren’t dangerous—they’re therapeutic.

They help restore mobility, reduce inflammation, and increase comfort in daily movement, even for people who’ve struggled with joint issues for years.

Improving Cardiovascular Health

Although squats are typically categorized as a resistance exercise, they can offer surprisingly powerful cardiovascular benefits—especially when performed with moderate to high reps, shortened rest periods, or as part of a circuit.

Unlike steady-state cardio, squatting under load activates large muscle groups simultaneously, forcing the heart and lungs to work harder to supply oxygen-rich blood throughout the body.

This full-body demand makes squats an effective tool for enhancing both aerobic capacity and cardiopulmonary efficiency when programmed correctly.

A 2024 study published in Scientific Reports showed that during five sets of squats at 65% of 1-rep max, trained individuals reached oxygen consumption levels up to 108% of their measured VO₂max, depending on their strength status (Hong et al., 2024).

This suggests that squatting at higher volumes or intensities can place a substantial aerobic demand on the body, especially in strong or well-conditioned individuals.

Additionally, squats stimulate cardiovascular adaptations by:

- Increasing heart rate and stroke volume

- Improving blood vessel elasticity and circulation

- Boosting post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC)

- Elevating metabolic rate and fat oxidation

High-rep squat variations like jump squats, air squats, goblet squats, and even barbell back squats performed in conditioning circuits can improve cardiovascular endurance, promote heart health, and increase work capacity—all without needing to spend hours on a treadmill or bike.

Whether you’re an athlete looking to improve recovery between sprints or a fitness enthusiast trying to burn fat and build endurance, squats can be a powerful—and underrated—tool for cardiovascular conditioning.

Types of Squats (With Unique Benefits)

Each squat variation offers unique benefits by shifting the load, altering joint angles, or emphasizing different muscle groups.

Incorporating a variety of squats into your training can improve muscular balance, movement quality, and athletic performance—while keeping training fresh and functional.

Below are 11 of the most effective squat variations, along with key form cues, primary muscle targets, and specific benefits.

Air Squats (Bodyweight Squats)

Air Squats (aka Bodyweight Squats) are a foundational lower-body exercise that use only your body weight to develop mobility, neuromuscular control, and muscular endurance.

They’re one of the best bodyweight exercises, perfect for beginners, warm-ups, or conditioning workouts with high volume and low impact.

How to Do It:

- Stand tall with feet shoulder-width apart. Initiate the squat by pushing your hips back and bending the knees.

- Keep your core tight, spine neutral, and descend as low as your mobility allows.

- Press through your heels to stand up.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, hamstrings, calves, core

Benefits of Air Squats:

- Teaches basic squat mechanics

- Improves mobility and movement efficiency

- Great for warm-ups, rehab, and conditioning circuits

- Low-impact and accessible for all levels

When to Use: Ideal for beginners, bodyweight circuits, active recovery, and mobility work.

Goblet Squats

Goblet Squats are performed by holding a dumbbell or kettlebell at chest height, helping improve posture, core engagement, and squat mechanics while building lower-body strength.

Goblet squats are ideal for learning proper form and progressing from bodyweight to loaded squats.

How to Do It:

- Hold a dumbbell or kettlebell close to your chest with elbows tucked.

- Perform a squat while keeping your torso upright and core braced.

- Drive through your heels to return to standing.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, adductors, core, upper back

Benefits:

- Encourages a more upright torso

- Improves squat depth and mobility

- Strengthens posture and core engagement

- Perfect stepping stone between air squats and barbell squats

When to Use: Great for teaching proper squat form, improving motor control, and building foundational strength.

Front Squats

Front Squats involve holding a barbell on the front of your shoulders, which shifts the load forward to emphasize your quads and core while promoting an upright torso.

Front squats are great for athletes and lifters focused on improving posture, mobility, and explosive leg strength.

How to Do It:

- Rest the barbell on the front deltoids with elbows high and chest tall.

- Squat down while keeping the spine neutral and torso vertical.

- Drive up through the heels while maintaining elbow position.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, erector spinae, core, upper back

Benefits:

- Increases quad and core activation

- Enhances thoracic spine and ankle mobility

- Reduces spinal compression compared to back squats

- Excellent for Olympic lifting and athletic development

When to Use: Ideal for athletes, those with knee-dominant goals, or anyone seeking a more upright squat position.

Back Squats

Back Squats place the barbell across your upper back or traps, allowing for heavier loading to build strength in the glutes, hamstrings, and spinal stabilizers.

Back squats are a classic strength-building lift and a cornerstone of athletic performance programs.

How to Do It:

- Place the barbell across your upper traps or rear delts (high-bar or low-bar).

- Brace your core, push your hips back, and squat down while keeping the spine aligned.

- Drive up through the heels and glutes.

Muscles Worked: Glutes, hamstrings, quads, spinal erectors, calves, core

Benefits:

- Allows for the heaviest loading potential

- Builds posterior chain strength and total-body mass

- Foundation for maximal strength development

- Versatile and scalable

When to Use: Best for athletes, powerlifters, and anyone building lower-body strength and size.

Jump Squats

Jump Squats are a plyometric version of the squat that adds an explosive jump at the top of each rep to develop power, speed, and reactive strength.

Jump squats also raise heart rate quickly, making them useful for conditioning and fat-burning workouts.

How to Do It:

- Start in a standing position.

- Lower into a squat, then explode upward into a jump, landing softly and immediately transitioning into the next rep.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, calves, core

Benefits:

- Improves explosive power

- Increased vertical jump

- Enhances fast-twitch muscle recruitment

- Builds reactive strength and athleticism

- Elevates heart rate for metabolic conditioning

When to Use: Use for plyometric training, contrast sets, or conditioning days.

Split Squats

Split Squats are a stationary lunge variation where one foot stays forward, and one stays back, targeting single-leg strength, balance, and joint stability.

Split squats are an excellent single-leg exercise for correcting muscle imbalances and improving hip mobility.

How to Do It:

- Stand in a lunge stance with one foot forward and one foot back.

- Lower your back knee toward the ground while keeping the front shin vertical.

- Drive through the front heel to rise.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, hamstrings, calves, core

Benefits:

- Improves single-leg strength and balance

- Addresses muscle imbalances and asymmetries

- Enhances hip mobility and ankle stability

- Low spinal load compared to bilateral squats

When to Use: Great for rehab, accessory leg work, or developing unilateral control.

Bulgarian Split Squats

Bulgarian Split Squats elevate the rear foot on a bench to increase the challenge to the front leg, significantly activating the quads and glutes while demanding balance and core stability.

Bulgarian split squats are one of the best single-leg exercises and a favorite among athletes for building unilateral power and leg size.

How to Do It:

- Elevate your rear foot on a bench or platform.

- Keep your chest upright and descend until the front thigh is parallel to the floor.

- Drive through the front foot to rise.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, hamstrings, core

Benefits:

- High glute and quad activation

- Demands balance, stability, and mobility

- Very effective for hypertrophy and unilateral strength

- Requires less weight for high stimulus

When to Use: Ideal for athletes, strength enthusiasts, and those with limited equipment or space.

Hack Squats

Hack Squats are a machine-based squat that fixes your movement path and isolates the quads by placing more emphasis on knee extension.

Hack squats are great for hypertrophy-focused training and minimizing strain on the lower back.

How to Do It:

- Performed on a hack squat machine.

- Position your back against the pad and shoulders under the shoulder pads.

- Descend into a squat while keeping your hips and spine against the pad, then push upward through your feet.

Muscles Worked: Quads (primarily), glutes, hamstrings

Benefits:

- Isolates the quads with less spinal loading

- Easier to control than free weight squats

- Ideal for hypertrophy training and pre-exhaust sets

- Great for beginners building lower-body size

When to Use: Best for bodybuilding programs, quad-focused leg days, or when free-weight squats are contraindicated.

Zercher Squats

Zercher Squats position the barbell in the crooks of your elbows in front of your body, forcing your core, upper back, and legs to work together to maintain posture and balance.

Zercher squats are highly functional and uniquely effective for developing total-body tension and bracing strength.

How to Do It:

- Hold a barbell in the crooks of your elbows, close to your torso.

- Maintain a strong core, descend into a squat with a vertical torso, and rise while keeping the bar stable.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, core, traps, biceps

Benefits:

- Challenges posture and upper back strength

- Builds core stability and bracing capacity

- Useful for combat athletes and functional fitness

- Encourages deep squat depth and form discipline

When to Use: Effective for athletes, strongman training, and those looking to improve upper-body posture during squats.

Box Squats

Box Squats use a box or bench as a depth target and cue for sitting back, helping improve posterior chain recruitment, squat mechanics, and explosive concentric force.

Box squats are useful for beginners learning depth control or athletes training for power and strength.

How to Do It:

- Set up a box or bench behind you.

- Squat back until your glutes touch the box, pause momentarily, then drive through the heels to stand.

- Keep shins vertical and engage the posterior chain.

Muscles Worked: Glutes, hamstrings, quads, core

Benefits:

- Teaches hip hinge and control

- Emphasizes posterior chain and explosive concentric force

- Reduces stress on knees with controlled depth

- Great for beginners or lifters relearning form

When to Use: Ideal for teaching mechanics, power development, or managing training volume.

Pistol Squats

Pistol Squats are an advanced single-leg exercise performed on one leg, requiring high levels of strength, balance, ankle mobility, and core stability.

Pistol squats are a true test of single-leg control and an excellent tool for mastering bodyweight strength.

Since you generally don’t need to do “weighted” pistol squats, they are one of the best bodyweight leg exercises.

How to Do It:

- Stand on one leg with the other extended in front.

- Lower yourself slowly into a full squat, keeping the heel down and torso upright.

- Press through the heel to return to standing.

Muscles Worked: Quads, glutes, hamstrings, calves, core

Benefits:

- Tests and builds maximal balance and coordination

- Develops single-leg strength and joint control

- Requires advanced mobility and stability

- Can be performed anywhere with no equipment

When to Use: Advanced athletes or bodyweight training enthusiasts working on control, resilience, and lower-body symmetry.

Cossack Squats

Cossack squats are a dynamic, mobility-focused squat variation that involves squatting laterally to one side while keeping the opposite leg extended.

They train the lower body through a different plane of motion than traditional squats, improving lateral strength, joint mobility, and hip stability.

How to Do Cossack Squats:

- Begin standing with your feet in a wide stance, toes pointed slightly outward.

- Shift your weight to one side, bending that knee and pushing your hips back while keeping the opposite leg straight.

- Lower your body as far as your mobility allows, keeping your chest up and both heels grounded (if possible).

- Push through the bent leg to return to the starting position and repeat on the other side.

Start with shallow depth and gradually increase your range of motion as your ankle, hip, and adductor mobility improve.

Muscles Worked:

- Quads (on the bent leg)

- Glutes and hamstrings

- Adductors (inner thighs)

- Calves and ankles

- Core and spinal stabilizers

Benefits of Cossack Squats:

- Improves hip, knee, and ankle mobility

- Enhances adductor flexibility and strength

- Builds lateral movement strength, crucial for athletes in multidirectional sports

- Identifies and corrects asymmetries between sides

- Increases control and balance through a wide range of motion

Cossack squats are especially valuable for athletes who need to move efficiently in multiple directions—like basketball, tennis, or soccer players.

They’re also excellent for anyone looking to increase squat depth, reduce injury risk, and develop more mobile and resilient joints.

Overhead Squats

Overhead squats are one of the most advanced and technically demanding squat variations, involving a barbell held overhead with arms fully extended throughout the entire movement.

They combine mobility, stability, and strength in a uniquely challenging way, making them a staple in Olympic weightlifting and functional fitness programs.

How to Do Overhead Squats:

- Start with the barbell in a wide snatch grip and press it overhead until your arms are fully locked out.

- Set your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width with toes turned slightly outward.

- Brace your core, pull your rib cage down, and keep your chest tall as you initiate the squat.

- Lower your hips by bending at the knees and hips while maintaining a vertical torso and keeping the bar directly over the midfoot.

- Descend until your hips drop below parallel, then drive through your heels to return to standing—keeping the bar stable overhead the entire time.

Good mobility in the shoulders, thoracic spine, hips, and ankles is essential to perform this movement safely and effectively.

Muscles Worked:

- Quads, glutes, hamstrings (primary movers)

- Shoulders, traps, upper back (stabilizers for overhead position)

- Core, spinal erectors, obliques (for postural control and balance)

Benefits of Overhead Squats:

- Enhances shoulder and thoracic mobility

- Improves core strength and full-body stability

- Reveals and corrects movement dysfunctions

- Builds exceptional balance, coordination, and control

- Transfers well to Olympic lifts like the snatch and clean & jerk

Due to their technical complexity, overhead squats are not typically used to build max strength, but they are invaluable for developing movement quality, functional mobility, and athletic awareness.

If you’re a weightlifter, CrossFitter, or athlete needing elite body control and mobility, this variation belongs in your rotation.

Final Thoughts: Are Squats the Best Leg Exercise?

Squats are more than a leg day staple—they’re a pillar of human movement, athletic excellence, and functional longevity. With dozens of variations available, there’s a squat for every body and every goal. A well-programmed squat routine is a non-negotiable foundation for anyone serious about their health, fitness, or sports performance.